Elon Musk Blog Series by Tim Urban

Summary: Wait But Why is my favorite blog on the internet. Elon Musk is my favorite human to learn about. Put together? This blog series is a total masterpiece. You’ll learn about science, engineering, first-principles thinking, and why the world’s raddest man is the way that he is. I particularly recommend the final post, entitled “The Cook and the Chef: Musk’s Secret Sauce.”

Rating: 10/10

5 Big Ideas:

Big Ideas

1. First Principles

First principles are the key truths underlying a particular domain. They are often the building blocks of knowledge. This is a physics concept. Physicists are known for using first principles (e.g. conservation of energy) and deriving powerful conclusions from those. Elon believes that you should treat knowledge as a semantic tree. Understand the key building blocks (i.e. the trunk) before you connect the branches, twigs, and leaves. Otherwise, they’ll have nothing to hold onto.

2. Your brain is software (and you should optimize it!)

Elon views humans as computers. Our physical hardware (brain and body) is equivalent to a computer’s hardware. Software is the information running on that hardware. “His software is the way he learns to think, his value system, his habits, his personality. And learning, for Musk, is simply the process of ‘downloading data and algorithms into your brain.'”

One should take a look at their software and decide where it ought to be revised or updated. What views, beliefs, or values would you like to update? What information would you like to download into your software?

3. Cooks vs. chefs

Cooks are simply those who follow a recipe. They are great at it and that is a very useful skill to have. However, to do revolutionary things, you need to be a chef. Chefs make the recipes. They look at the world and envision something that doesn’t exist yet. Then, using their knowledge of first principles, they try a solution that might work. Chefs test and tinker with things until they develop an innovative solution.

Many people believe that the only way things can be is the way that things already are. They also don’t question things too much. If everyone around them believes that a certain thing is true, they accept it as fact. This is a cook mentality. Chefs question everything. They wonder whether things are really true and try to reason it out on their own, rather than simply following the herd. When they see something being done a particular way, they wonder if it couldn’t be done differently or better.

4. Fear and risk

“When I was a little kid, I was really scared of the dark. But then I came to understand, dark just means the absence of photons in the visible wavelength—400 to 700 nanometers. Then I thought, well it’s really silly to be afraid of a lack of photons. Then I wasn’t afraid of the dark anymore after that.” -Elon Musk

Most of us don’t view fear accurately. We fear things that aren’t actually dangerous. Elon likes to look at fears very analytically. Darkness, for instance, is nothing to be afraid of. It is simply fear of a lack of photons. Similarly, starting a company can feel incredibly scary and risky. But what is truly the worst-case scenario? That you would be eating ramen and sleeping on your parents couch? That doesn’t sound so scary (or maybe it does lol).

5. How to achieve your goals

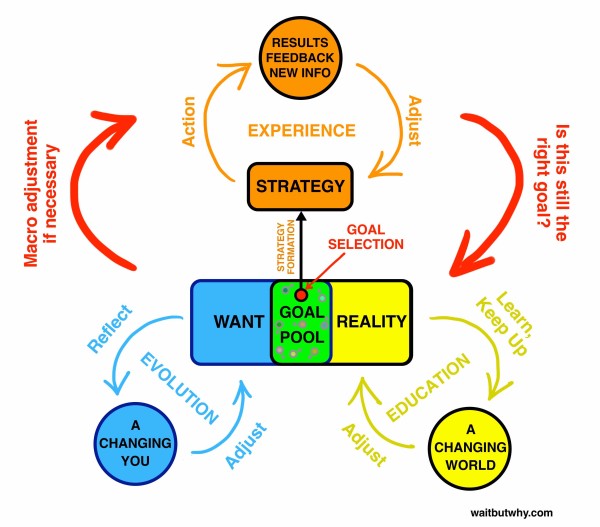

Elon views goals like the above chart. He sees a thing he wants and wonders if it could be possible. He analyzes that against what is possible in reality. For instance, is it actually impossible to create a reusable rocket, or just really hard? Then he formulates a strategy and executes on it. As each of these things happens, he is making micro-adjustments, tweaking things, and considering whether goals should change. Read the whole post to get a deeper understanding of the way that Elon views goals. I thought it was tremendous.

Kindle Highlights:

One thing you’ll learn about Musk as you read these posts is that he thinks of humans as computers, which, in their most literal sense, they are. A human’s hardware is his physical body and brain. His software is the way he learns to think, his value system, his habits, his personality. And learning, for Musk, is simply the process of “downloading data and algorithms into your brain.”

In 2002, before the sale of PayPal even went through, Musk starting voraciously reading about rocket technology, and later that year, with $100 million, he started one of the most unthinkable and ill-advised ventures of all time: a rocket company called SpaceX, whose stated purpose was to revolutionize the cost of space travel in order to make humans a multi-planetary species by colonizing Mars with at least a million people over the next century.

He sees advertising as manipulative and dishonest.

The way I approach a post like that is I’ll start with the surface of the topic and ask myself what I don’t fully get—I look for those foggy spots in the story where when someone mentions it or it comes up in an article I’m reading, my mind kind of glazes over with a combination of “ugh it’s that icky term again nah go away” and “ew the adults are saying that adult thing again and I’m seven so I don’t actually understand what they’re talking about.” Then I’ll get reading about those foggy spots—but as I clear away fog from the surface, I often find more fog underneath. So then I research that new fog, and again, often come across other fog even further down. My perfectionism kicks in and I end up refusing to stop going down the rabbit hole until I hit the floor.

I’ve heard people compare knowledge of a topic to a tree. If you don’t fully get it, it’s like a tree in your head with no trunk—and without a trunk, when you learn something new about the topic—a new branch or leaf of the tree—there’s nothing for it to hang onto, so it just falls away. By clearing out fog all the way to the bottom, I build a tree trunk in my head, and from then on, all new information can hold on, which makes that topic forever more interesting and productive to learn about. And what I usually find is that so many of the topics I’ve pegged as “boring” in my head are actually just foggy to me—like watching episode 17 of a great show, which would be boring if you didn’t have the tree trunk of the back story and characters in place.

Energy being “the property of matter and radiation that is manifest as a capacity to perform the exertion of force overcoming resistance or producing molecular change.” That was pretty unfun, so for our purposes, let’s call energy “the thing that lets something do stuff.”

Almost all of the energy used by the Earth’s living things got to us in the first place from the sun.2 The sun’s energy is what makes the wind blow and the rain fall and it’s what powers the Earth’s living things—the biosphere.

That’s how food is invented—plants know how to take the sun’s joules and turn them into food. At that point, all hell breaks loose as everyone starts murdering everyone else so they can steal their joules.

Fire joules were hard to harness, but if you sent them into water, they’d get the water molecules to increasingly freak out and bounce around until finally those molecules would fully panic and start flying off the surface, evaporating upwards with the force of the raging fire below. You’d have successfully converted the thermal energy joules of the fire—which we didn’t know how to directly harness—into a powerful jet of steam we could control.

The way capitalism theoretically works is that the more real-world value you create, the more money you’ll make.

“A company like GM is a finance-driven company who always has to live up to financial expectations. Here we look at it the other way around—the product is successful when it’s great, and the company becomes great because of that.” (This mirrored what Musk had told me earlier in the day: “The moment the person leading a company thinks numbers have value in themselves, the company’s done. The moment the CFO becomes CEO—it’s done. Game over.”)

The Model S would be Tesla’s first flagship product, and it was their chance to reinvent the concept of a car, from scratch. Von Holzhausen said, “When we started Model S, it was a clean sheet of paper.”

This all sounded uncannily similar to how Steve Jobs had done things at Apple. He obsessed over making “insanely great products,” and he never paid attention to what other companies were doing, always coming at things from a clean sheet of paper perspective. When Apple decided to make a phone, they didn’t try to make a better Blackberry—they asked, “What should a mobile phone be?”

The Tesla battery is heavy and they wanted to make the body super light to offset some of that weight—so they turned to SpaceX and used its advanced rocket technology to make Tesla the only North American car with an all aluminum body.

They didn’t like the dealership model and wanted to sell directly to customers, but many states don’t allow that, so one by one, they’re fighting the states that won’t and slowly overturning direct car sales bans.

“I don’t know what a business is. All a company is is a bunch of people together to create a product or service. There’s no such thing as a business, just pursuit of a goal—a group of people pursuing a goal.”

“The factory is a temple devoted to what SpaceX sees as its major weapon in the rocket-building game, in-house manufacturing. SpaceX manufactures between 80 percent and 90 percent of its rockets, engines, electronics, and … designs its own motherboards and circuits, sensors to detect vibrations, flight computers, and solar panels.” Old-fashioned industrialists, like Andrew Carnegie and Henry Ford, were all about vertical integration, as is Apple today in many ways. Most of today’s companies avoid taking on the massive scope vertical integration requires, but for a quality control freak, like Musk or Jobs, it’s the only way they’d have it.

“I know my rocket inside out and backward. I can tell you the heat treating temper of the skin material, where it changes, why we chose that material, the welding technique…down to the gnat’s ass.”

The point of almost any space launch is to take something to space. The thing you’re taking is called the payload.

In order to survive the rough trip to space, the payload is sometimes inside a protective shell called a fairing.

The only companies in aerospace are huge, and huge companies are risk averse. He says, “There’s a tremendous bias against taking risks. Everyone is trying to optimize their ass-covering

Not enough vertical integration.

“There’s this tendency of big aerospace companies to outsource everything … They outsource to subcontractors, and then the subcontractors outsource to sub-subcontractors, and so on. You have to go four or five layers down to find somebody actually doing something useful—actually cutting metal, shaping atoms. Every level above that tacks on profit—it’s overhead to the fifth power.”

The space launch industry is like a handful of auto mechanics in a small town that all charge about ten times as much as they need to, but because A) customers are clueless about the process and what it should cost, and B) all the competition overcharges as well, there’s no incentive to upgrade equipment, increase efficiency, and bring down costs. SpaceX is like a newcomer to town who sets up an auto shop, comes up with newer, better ways to fix cars, works harder than anyone else, and is able to charge a fraction of the price for the same service. Which ruins everything for the town’s other auto mechanics.

But the scientists started the game with no rules at all. The puzzle was a blank slate where any observations and measurements they found were welcome.

When it comes to most of the way we think, the way we make decisions, and the way we live our lives, we’re much more like the flood geologists than the science geologists. And Elon’s secret? He’s a scientist through and through.

MuskSpeak is a language that describes everyday parts of life as exactly what they actually, literally are.

When you or I look at kids, we see small, dumb, cute people. When Musk looks at his five kids, he sees five of his favorite computers.

At its simplest definition, a computer is an object that can store and process data—which the brain certainly is.

When people think about what makes someone like Elon Musk so effective, they often focus on the hardware—and Musk’s hardware has some pretty impressive specs. But the more I learn about Musk and other people who seem to have superhuman powers—whether it be Steve Jobs, Albert Einstein, Henry Ford, Genghis Khan, Marie Curie, John Lennon, Ayn Rand, or Louis C.K.—the more I’m convinced that it’s their software, not their natural-born intelligence or talents, that makes them so rare and so effective.

The structure of Musk’s software starts like many of ours, with what we’ll call the Want box: This box contains anything in life where you want Situation A to turn into Situation B. Situation

And how do you cause something to change? You direct your power towards it. A person’s power can come in various forms: your time, your energy (mental and physical), your resources, your persuasive ability, your connection to others, etc.

“Science is a way of thinking much more than it is a body of knowledge”

He builds each software component himself, from the ground up. Musk calls this “reasoning from first principles.” I’ll let him explain: I think generally people’s thinking process is too bound by convention or analogy to prior experiences. It’s rare that people try to think of something on a first principles basis. They’ll say, “We’ll do that because it’s always been done that way.” Or they’ll not do it because “Well, nobody’s ever done that, so it must not be good.” But that’s just a ridiculous way to think. You have to build up the reasoning from the ground up—“from the first principles” is the phrase that’s used in physics. You look at the fundamentals and construct your reasoning from that, and then you see if you have a conclusion that works or doesn’t work, and it may or may not be different from what people have done in the past.

Brain software has four major decision-making centers: 1) Filling in the Want box 2) Filling in the Reality box 3) Goal selection from the Goal Pool 4) Strategy formation

He continually adjusts each component’s conclusions as new information comes in.

Richard Feynman has said, “Scientific knowledge is a body of statements of varying degrees of certainty—some most unsure, some nearly sure, none absolutely certain.”

But the goal-achievement strategy you came up with was just your first crack. It was a hypothesis, ripe for testing. You test a strategy hypothesis one way: action. You pour your power into the strategy and see what happens. As you do this, data starts flowing in—results, feedback, and new information from the outside world. Certain parts of your strategy hypothesis might be strengthened by this new data, others might be weakened, and new ideas may have sprung to life in your head through the experience—but either way, some adjustment is usually called for: As this strategy loop spins and your power becomes more and more effective at accomplishing your goal, other things are happening down below.

I was at one point thinking about doing physics as a career—I did undergrad in physics—but in order to really advance physics these days, you need the data. Physics is fundamentally governed by the progress of engineering. This debate—“Which is better, engineers or scientists? Aren’t scientists better? Wasn’t Einstein the smartest person?”—personally, I think that engineering is better because in the absence of the engineering, you do not have the data.

Musk says that in college, he thought hard about the first principles question, “What will most affect the future of humanity?” and put together a list of five things: “the internet; sustainable energy; space exploration, in particular the permanent extension of life beyond Earth; artificial intelligence; and reprogramming the human genetic code.”

Conventional wisdom screamed at the top of its lungs for him to stop. It said he had no formal education in the field and didn’t know the first thing about being a rocket scientist. But his software told him that formal education was just another way to download information into your brain and “a painfully slow download” at that—so he started reading, meeting people, and asking questions. Conventional wisdom said no entrepreneur had ever succeeded at an endeavor like this before, and that he shouldn’t risk his money on something so likely to fail. But Musk’s stated philosophy is, “When something is important enough, you do it even if the odds are not in your favor.”

Historically, all rockets have been expensive, so therefore, in the future, all rockets will be expensive. But actually that’s not true. If you say, what is a rocket made of? It’s made of aluminum, titanium, copper, carbon fiber. And you can break it down and say, what is the raw material cost of all these components? And if you have them stacked on the floor and could wave a magic wand so that the cost of rearranging the atoms was zero, then what would the cost of the rocket be? And I was like, wow, okay, it’s really small—it’s like 2% of what a rocket costs. So clearly it would be in how the atoms are arranged—so you’ve got to figure out how can we get the atoms in the right shape much more efficiently. And so I had a series of meetings on Saturdays with people, some of whom were still working at the big aerospace companies, just to try to figure out if there’s some catch here that I’m not appreciating. And I couldn’t figure it out. There doesn’t seem to be any catch. So I started SpaceX.

He used the same first principles logic and a calculator to determine that most of the problem was the cost of middlemen, not raw materials, and decided that actually, conventional wisdom was wrong and batteries could be much cheaper in the future. So he co-founded Tesla with the mission of accelerating the advent of a mostly-electric-vehicle world—first by pouring in resources power and funding the company, and later by contributing his time and energy resources as well and becoming CEO.

There are all kinds of tech companies that build software. They think hard, for years, about the best, most efficient way to make their product. Musk sees people as computers, and he sees his brain software as the most important product he owns—and since there aren’t companies out there designing brain software, he designed his own, beta tests it every day, and makes constant updates. That’s why he’s so outrageously effective, why he can disrupt multiple huge industries at once, why he can learn so quickly, strategize so cleverly, and visualize the future so clearly. This part of what Musk does isn’t rocket science—it’s common sense. Your entire life runs on the software in your head—why wouldn’t you obsess over optimizing it? And yet, not only do most of us not obsess over our own software—most of us don’t even understand our own software, how it works, or why it works that way. Let’s try to figure out why.

Everyone’s raised differently, but for most people I know, it went something like this: We were taught all kinds of things by our parents and teachers—what’s right and wrong, what’s safe and dangerous, the kind of person you should and shouldn’t be. But the idea was: I’m an adult so I know much more about this than you, it’s not up for debate, don’t argue, just obey. That’s when the cliché “Why?” game comes in (what ElonSpeak calls “the chained why”). A child’s instinct isn’t just to know what to do and not to do, she wants to understand the rules of her environment. And to understand something, you have to have a sense of how that thing was built. When parents and teachers tell a kid to do XYZ and to simply obey, it’s like installing a piece of already-designed software in the kid’s head. When kids ask Why? and then Why? and then Why?, they’re trying to deconstruct that software to see how it was built—to get down to the first principles underneath so they can weigh how much they should actually care about what the adults seem so insistent upon. The first few times a kid plays the Why game, parents think it’s cute. But many parents, and most teachers, soon come up with a way to cut the game off: Because I said so. “Because I said so” inserts a concrete floor into the child’s deconstruction effort below which no further Why’s may pass. It says, “You want first principles? There. There’s your floor. No more Why’s necessary. Now fucking put your boots on because I said so and let’s go.”

And when that’s the way we’re brought up, we end up with a bucket of fish and no rod—a piece of installed software that we’ve learned how to use, but no ability to code anything ourselves.

“non-creative behavior is learned.”

someone really grilled you on your reasons and on the reasoning beneath them, you end up in a confusing place. It gets confusing way down there because the first principles foundation at the bottom is a mishmash of the values and beliefs of a bunch of people from different generations and countries—a bunch of people who aren’t you.

I don’t know what’s the matter with people: they don’t learn by understanding, they learn by some other way—by rote or something. Their knowledge is so fragile! —Richard Feynman

Some things I think are very conservative, or very liberal. I think when someone falls into one category for everything, I’m very suspicious. It doesn’t make sense to me that you’d have the same solution to every issue. —Louis C.K.

What most dogmatic thinking tends to boil down to is another good Seth Godin phrase: People like us do stuff like this.

Tribalism is good when the tribe and the tribe member both have an independent identity and they happen to be the same.

Tribalism is bad when the tribe and tribe member’s identity are one and the same.

The next time you’re with a member of a tribe you’re a part of, express a change of heart that aligns you on a certain topic with whoever your tribe considers to be Them. If you’re a religious Christian, tell people at church you’re not sure anymore that there’s a God.

If you’re in a tribe with a blind mentality of total certainty, you’ll probably see a look of horror. It won’t just seem wrong, it’ll seem like heresy. They might get angry, they might passionately try to convince you otherwise, they might cut off the conversation—but there will be no open-minded conversation. And because identity is so intertwined with beliefs in blind tribalism, the person actually might feel less close to you afterwards.

Everything you eat—every part of every cuisine we know so well—was at some point in the past created for the first time. Wheat, tomatoes, salt, and milk go back a long time, but at some point, someone said, “What if I take those ingredients and do this…and this…..and this……” and ended up with the world’s first pizza. That’s the work of a chef. Since then, god knows how many people have made a pizza. That’s the work of a cook.

The chef reasons from first principles, and for the chef, the first principles are raw edible ingredients. Those are her puzzle pieces, her building blocks, and she works her way upwards from there, using her experience, her instincts, and her taste buds. The cook works off of some version of what’s already out there—a recipe of some kind, a meal she tried and liked, a dish she watched someone else make.

he switches on the active decision-making part of his software and starts to go to work. He looks at what data he has and seeks out what more he needs. He thinks about the current state of the world and reflects on where his values and priorities lie. He gathers together those relevant first principles ingredients and starts puzzling together a reasoning pathway. It takes some hard work, but eventually, the pathway brings him to a hypothesis. He knows it’s probably wrong-ish, and as new data emerges, he’ll “taste-test” the hypothesis and adjust it.

Chefs aren’t guaranteed to do anything good, but when there’s a little talent and a lot of persistence, they’re almost certain to make a splash. Sometimes the chef is the one brave enough to go for something big—but other times, someone doesn’t feel the desire to make a splash and the chef is the one with the strength of character to step out of the game and in favor of keeping it small. Being a chef isn’t being like Elon Musk—it’s being yourself. No one talks about the “reasoning industry,” but we’re all part of it, and when it comes to chefs and cooks, it’s no different than any other industry. We’re working in the reasoning industry every time we make a decision. Your current life, with all its facets and complexity, is like a reasoning industry album. The question is, how did that set of songs come to be? How were the songs composed, and by whom? And in those critical do-or-die moments when it’s time to write a new song, how do you do your creating? Do you dig deep into yourself? Do you start with the drumbeat and chords of an existing song and write your own melody on top of it? Do you just play covers? I know what you want the answers to these questions to be. This is a straightforward one—it’s clearly better to be a chef. But unlike the case with most major distinctions in life—hard-working vs. lazy, ethical vs. dishonest, considerate vs. selfish—when the chef/cook distinction passes right in front of us, we often don’t even notice it’s there.

In order to form an immaculate member of a flock of sheep one must, above all, be a sheep. In other words, you might be a star and a leader in your world or in the eyes of your part of society, but if the core reason you picked that goal in the first place was because your tribe’s cookbook says that it’s an impressive thing and it makes the other tribe members gawk, you’re not being a leader—you’re being a super-successful follower. And, as Einstein says, no less of a cook than all those whom you’ve impressed.

The way we see it, we’re all a bunch of independent-thinking chefs—and it’s just that Musk is a really impressive chef. Which is both A) overrating Musk and B) overrating ourselves. And completely missing the real story. Musk is an impressive chef for sure, but what makes him such an extreme standout isn’t that he’s impressive—it’s that most of us aren’t chefs at all. It’s like a bunch of typewriters looking at a computer and saying, “Man, that is one talented typewriter.”

So when Musk put his entire fortune down and on SpaceX and Tesla, he was being bold as fuck, but courageous? Not the right word. It was a case of a chef taking a bunch of information he had and puzzling together a plan that seemed logical. It’s not that he was sure he’d succeed—in fact, he thought SpaceX in particular had a reasonable probability of failure—it’s just that nowhere in his assessments did he foresee danger.

People believe thinking outside the box takes intelligence and creativity, but it’s mostly about independence.

When you’re in a foreign country and you decide to ditch the guidebook and start wandering aimlessly and talking to people, unique things always end up happening. When people hear about those things, they think of you as a pro traveler and a bold adventurer—when all you really did is ditch the guidebook.

When the American forefathers found themselves with a new country on their hands, they didn’t ask, “What should the rules be for selecting our king, and what should the limitations of his power be?” A king to them was what a physical keyboard was to Apple. Instead, they asked, “What should a country be and what’s the best way to govern a group of people?”

We spent this whole time trying to figure out the mysterious workings of the mind of a madman genius only to realize that Musk’s secret sauce is that he’s the only one being normal.

Anytime there’s a curious phenomenon within humanity—some collective insanity we’re all suffering from—it usually ends up being evolution’s fault. This story is no different. When it comes to reasoning, we’re biologically inclined to be cooks, not chefs, which relates back to our tribal evolutionary past.

That’s what Stephen Hawking meant when he said, “The greatest enemy of knowledge is not ignorance, it is the illusion of knowledge.”

If you want to see the lab mentality at work, just search for famous quotes of any prominent scientist and you’ll see each one of them expressing the fact that they don’t know shit. Here’s Isaac Newton: To myself I am only a child playing on the beach, while vast oceans of truth lie undiscovered before me. And Richard Feynman: I was born not knowing and have had only a little time to change that here and there. And Niels Bohr: Every sentence I utter must be understood not as an affirmation, but as a question. Musk has said his own version: You should take the approach that you’re wrong. Your goal is to be less wrong.

Eventually, we might wake up one day feeling like Breaking Bad’s Walter White, when he said, “Sometimes I feel like I never actually make any of my own… choices. I mean, my entire life it just seems I never… had a real say about any of it.” If we want to understand our own thinking, we have to stop being the dumb user of our own software and start being the pro—the auto mechanic, the electrician, the computer geek.

It’s time to roll up our sleeves, pop open the hood, and get our hands dirty with a bunch of not-that-fun questions about what we truly want, what’s truly possible, and whether the way we’re living our lives follows logically from those things. With each of these questions, the challenge is to keep asking why until you hit the floor—and the floor is what will tell you whether you’re in a church or a lab for that particular part of your life.

The thing you really want to look closely for is unjustified certainty. Where in life do you feel so right about something that it doesn’t qualify as a hypothesis or even a theory, but it feels like a proof? When there’s proof-level certainty, it means either there’s some serious concrete and verified data underneath it—or it’s faith-based dogma.

“This doesn’t seem right to me but everyone else says it’s right so it must be right and I’ll just pretend I also think it’s right so no one realizes I’m stupid” phenomenon. My favorite all-time quote might be Steve Jobs saying this: When you grow up, you tend to get told the world is the way it is and your life is just to live your life inside the world. Try not to bash into the walls too much. Try to have a nice family life, have fun, save a little money. That’s a very limited life. Life can be much broader once you discover one simple fact. And that is: Everything around you that you call life was made up by people that were no smarter than you. And you can change it, you can influence it, you can build your own things that other people can use. Once you learn that, you’ll never be the same again.

Being a gamechanger is just having little enough respect for the game that you realize there’s no good reason not to change the rules. Being a trailblazer is just not respecting the beaten path and so deciding to blaze yourself a new one. Being a groundbreaker is just knowing that the ground wasn’t laid by anyone that impressive and so feeling no need to keep it intact.

And yet, the delusion that society knows shit that you don’t runs deep, and still, somewhere in the back of your head, you don’t think it’s realistic that you could ever actually build that company, achieve that fabulous wealth or celebrity-status, create that TV show, win that senate campaign—no matter what it seems like.

It’s a confidence that says, “I may not know much, but no one else does either, so I might as well be the most knowledgeable person on Earth.”

Without the blissful arrogance of Proud Cook, Insecure Cook is lost in the world, wondering why he’s too dumb to get what everyone else gets and trying to watch others to figure out what he’s supposed to do—all while hoping nobody finds out that he doesn’t get it.

I’m a huge believer in taking feedback. I’m trying to create a mental model that’s accurate, and if I have a wrong view on something, or if there’s a nuanced improvement that can be made, I’ll say, “I used to think this one thing that turned out to be wrong—now thank goodness I don’t have that wrong belief.”

Failure is simply the opportunity to begin again, this time more intelligently. —Henry Ford Success is going from failure to failure without losing your enthusiasm. —Winston Churchill13 I have not failed 700 times. I’ve succeeded in proving 700 ways how not to build a lightbulb. —Thomas Edison

scientists learn through failure. Failure is a critical part of their process.

Humans are programmed to take fear very seriously, and evolution didn’t find it efficient to have us assess and re-assess every fear inside of us. It went instead with the “better safe than sorry” philosophy—i.e. if there’s a chance that a certain fear might be based on real danger, file it away as a real fear, just in case, and even if you confirm later that a fear of yours has no basis, keep it with you, just in case. Better safe than sorry.

The purpose of all of that fear is to make us protect ourselves from danger. The problem for us is that as far as evolution is concerned, danger = something that hurts the chance that your genes will move on—i.e., danger = not mating or dying or your kids dying, and that’s about it.

We’re more afraid of public speaking than texting on the highway, more afraid of approaching an attractive stranger in a bar than marrying the wrong person, more afraid of not being able to afford the same lifestyle as our friends than spending 50 years in a meaningless career—all because embarrassment, rejection, and not fitting in really sucked for hunters and gatherers.

The second major problem for Self-Loathing Cook is that, like all cooks, he can’t wrap his head around the fact that he’s the scientist in the lab—not the experiment. As we established earlier, conscious tribe members reach conclusions, while blind tribe members are conclusions. And what you believe, what you stand for, and what you choose to do each day are conclusions that you’ve drawn. In some cases, very, very publicly. As far as society is concerned, when you give something a try—on the values front, the fashion front, the religious front, the career front—you’ve branded yourself. And since people like to simplify people in order to make sense of things in their own head, the tribe around you reinforces your brand by putting you in a clearly-labeled, oversimplified box. What this all amounts to is that it becomes very painful to change. Changing is icky for someone whose identity will have to change along with it. And others don’t make things any easier. Blind tribe members don’t like when other tribe members change—it confuses them, it forces them to readjust the info in their heads, and it threatens the simplicity of their tribal certainty.

Referring to the aerospace industry, Musk said, “There’s a tremendous bias against taking risks. Everyone is trying to optimize their ass-covering.”

So what Self-Loathing Cook has to ask himself is: “Am I trapped in my own history?”

the epiphany that neither failing nor changing is actually a big deal can only be observed by experiencing it for yourself.

The challenge with this last epiphany is to somehow figure out a way to lose respect for your own fear. That respect is in our wiring, and the only way to weaken it is by defying it and seeing, when nothing bad ends up happening, that most of the fear you’ve been feeling has just been a smoke and mirrors act. Doing something out of your comfort zone and having it turn out okay is an incredibly powerful experience, one that changes you—and each time you have that kind of experience, it chips away at your respect for your brain’s ingrained, irrational fears.

Because the most important thing the chef knows that the cooks don’t is that real life and Grand Theft Auto aren’t actually that different.

If someone gave you a perfect simulation of today’s world to play in and told you that it’s all fake with no actual consequences—with the only rules being that you can’t break the law or harm anyone, and you still have to make sure to support your and your family’s basic needs—what would you do? My guess is that most people would do all kinds of things they’d love to do in their real life but wouldn’t dare to try, and that by behaving that way, they’d end up quickly getting a life going in the simulation that’s both far more successful and much truer to themselves than the real life they’re currently living. Removing the fear and the concern with identity or the opinions of others would thrust the person into the not-actually-risky Chef Lab and have them bouncing around all the exhilarating places outside their comfort zone—and their lives would take off. That’s the life irrational fears block us from. When I look at the amazing chefs of our time, what’s clear is that they’re more or less treating real life as if it’s Grand Theft Life. And doing so gives them superpowers. That’s what I think Steve Jobs meant all the times he said, “Stay hungry. Stay foolish.” And that’s what this third epiphany is about: fearlessness.

So if we want to think like a scientist more often in life, those are the three key objectives—to be humbler about what we know, more confident about what’s possible, and less afraid of things that don’t matter.

he was a master at looking at the world, asking “What’s really going on here?” and seeing the real answer. That’s why his story resonated so hard with me and why I dedicated so much Wait But Why time to this series.