Computer Systems - A Programmer's Perspective

Summary: CS:APP is a classic computer science book. In my effort to learn the fundamentals of computer science, CS:APP came up as one a primary resource for learning the core of CS.

Reading CS:APP really leveled up my understanding of what's under the hood of a computer system. In particular, I loved learning about bits and bytes. Specifically, the way that different data is encoded into binary. Everything on a computer is just 0's and 1's at the end of the day, it's just that the 0's and 1's are combined in clever ways to represent text, integers, floating points, colors, sound, video, pixels, etc. Going through the exercise of generating a binary encoding for unsigned integers, for example, is a useful way to understand these 0's and 1's can be used to represent more complex data.

Plus, the book dives into how assembly code works, the inner workings of computers, performance optimizations, and the memory heirarchy. All in all, this was a highly useful read.

Note that the guide I've been following to execute a personal CS curriculum, teachyourselfcs suggested reading the first 6 chapters of the book to ingest the primary benefits.

Rating: 9/10

Chapters

1. A Tour of Computer Systems

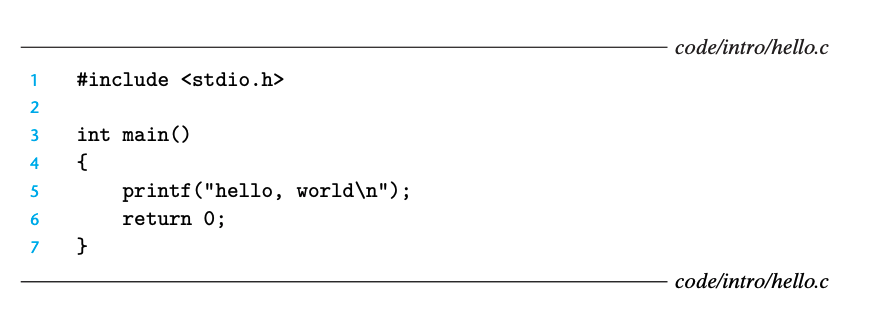

Our hello program begins life as a source program (or source file) that the programmer creates with an editor and saves in a text file called hello.c. The source program is a sequence of bits, each with a value of 0 or 1, organized in 8-bit chunks called bytes. Each byte represents some text character in the program.

All information in a system—including disk files, programs stored in memory, user data stored in memory, and data transferred across a network—is represented as a bunch of bits.

A file is a sequence of bytes, nothing more and nothing less. Every I/O device, including disks, keyboards, displays, and even networks, is modeled as a file. All input and output in the system is performed by reading and writing files, using a small set of system calls known as Unix I/O.

2. Representing and Manipulating Information

Modern computers store and process information represented as 2-valued signals. These lowly binary digits, or bits, form the basis of the digital revolution.

In isolation, a single bit is not very useful. When we group bits together and apply some interpretation that gives meaning to the different possible bit patterns, however, we can represent the elements of any finite set. For example, using a binary number system, we can use groups of bits to encode nonnegative numbers. By using a standard character code, we can encode the letters and symbols in a document.

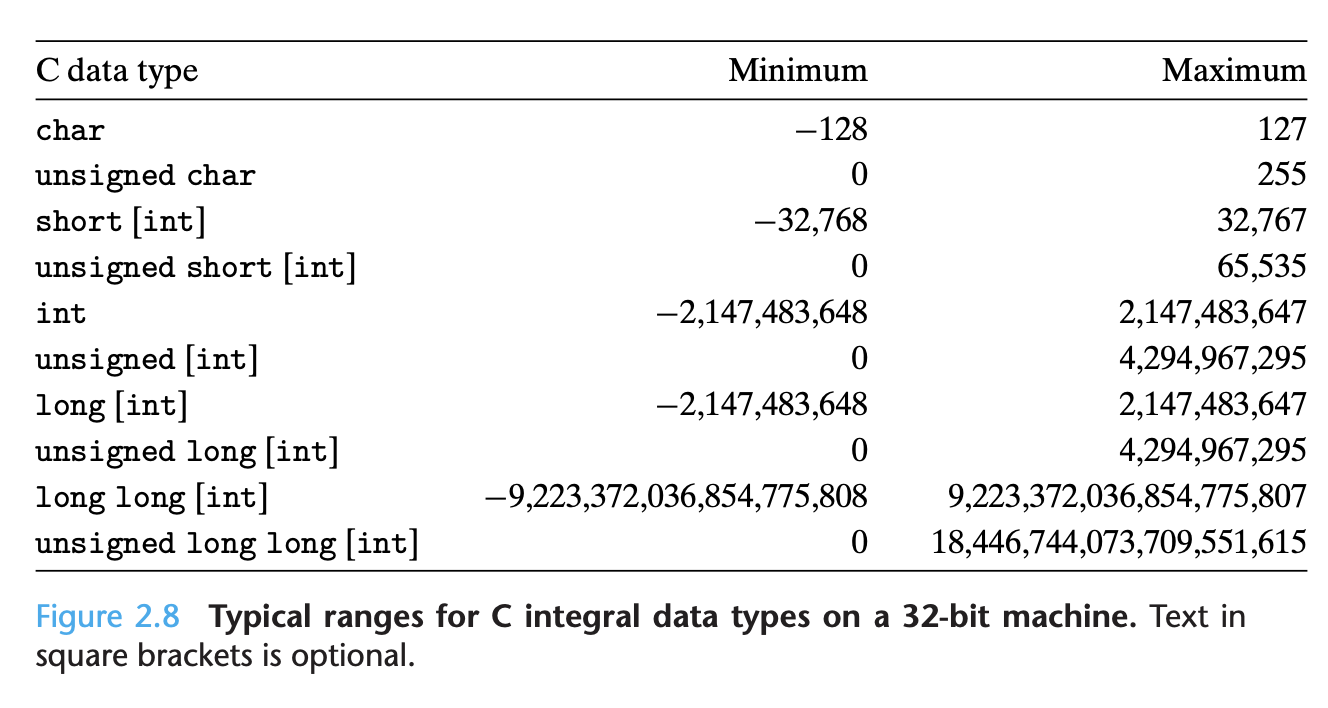

By studying the actual number representations, we can understand the ranges of values that can be represented and the properties of the different arithmetic operations. This understanding is critical to writing programs that work correctly over the full range of numeric values and that are portable across different combi- nations of machine, operating system, and compiler. As we will describe, a number of computer security vulnerabilities have arisen due to some of the subtleties of computer arithmetic.

Rather than accessing individual bits in memory, most computers use blocks of eight bits, or bytes, as the smallest addressable unit of memory. A machine-level program views memory as a very large array of bytes, referred to as virtual memory. Every byte of memory is identified by a unique number, known as its address, and the set of all possible addresses is known as the virtual address space.

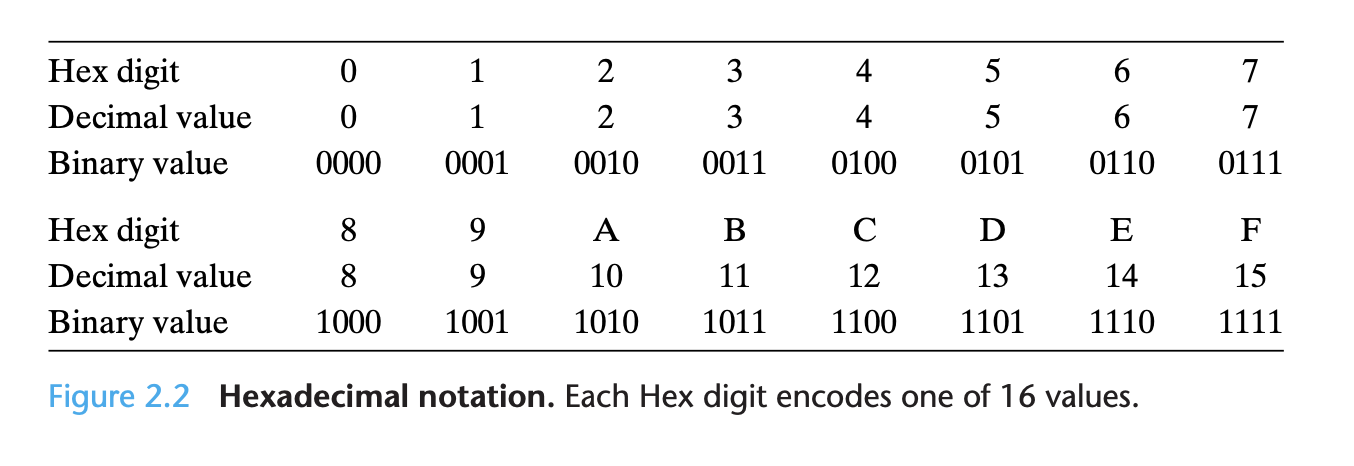

Hexidecimal notation:

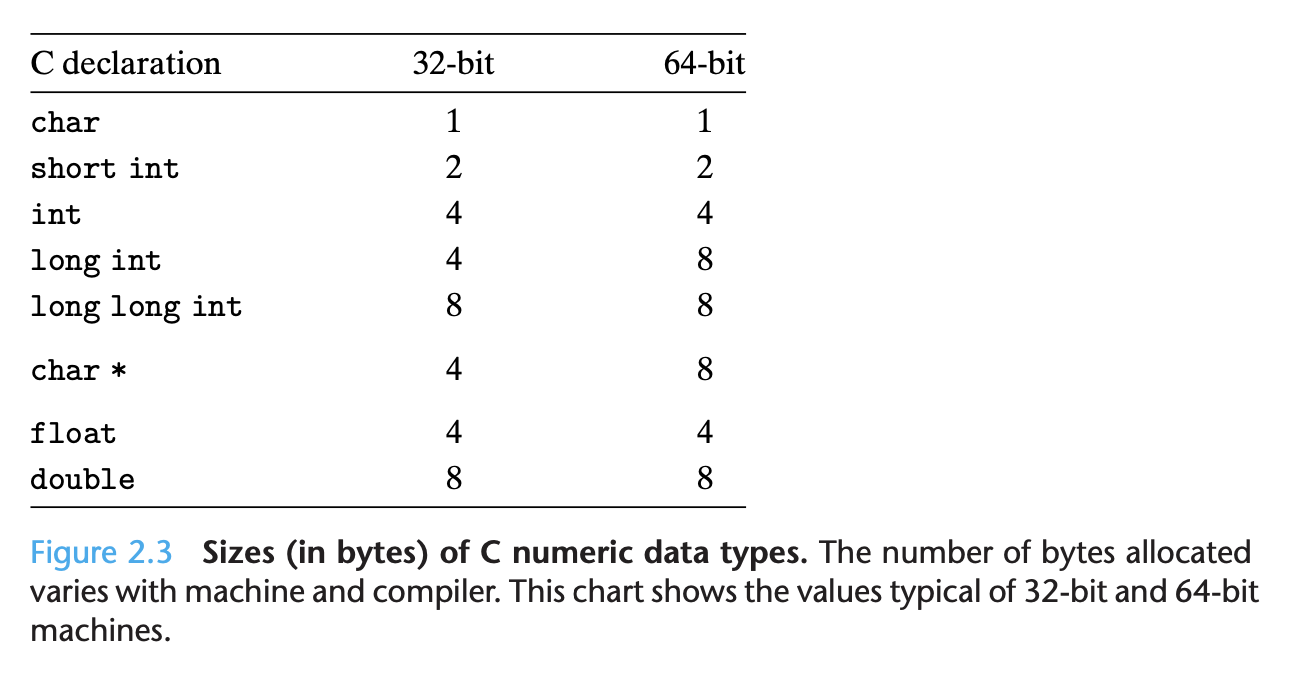

Word size: Every computer has a word size, indicating the nominal size of integer and pointer data. Since a virtual address is encoded by such a word, the most important system parameter determined by the word size is the maximum size of the virtual address space. That is, for a machine with a w-bit word size, the virtual addresses can range from 0 to 2w − 1, giving the program access to at most 2w bytes.

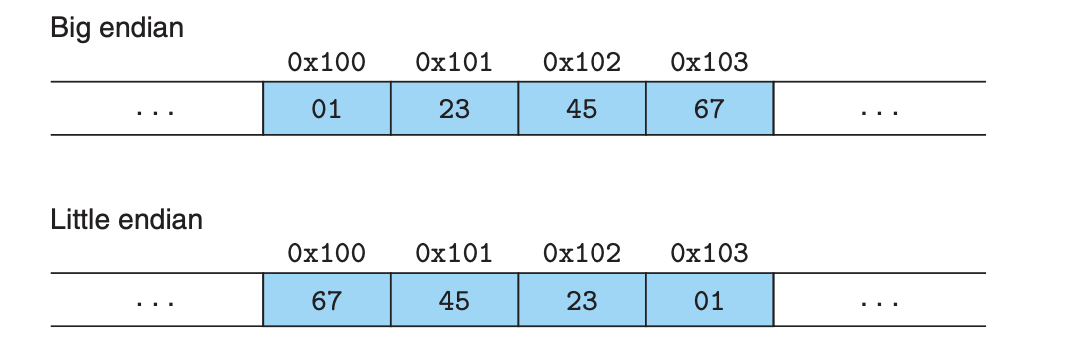

Byte ordering: The convention where the least significant byte comes first is referred to as little endian. This convention is followed by most Intel-compatible machines. The convention where the most significant byte comes first is referred to as big endian.

Representing Strings

A string in C is encoded by an array of characters terminated by the null (having value 0) character. Each character is represented by some standard encoding, with the most common being the ASCII character code.

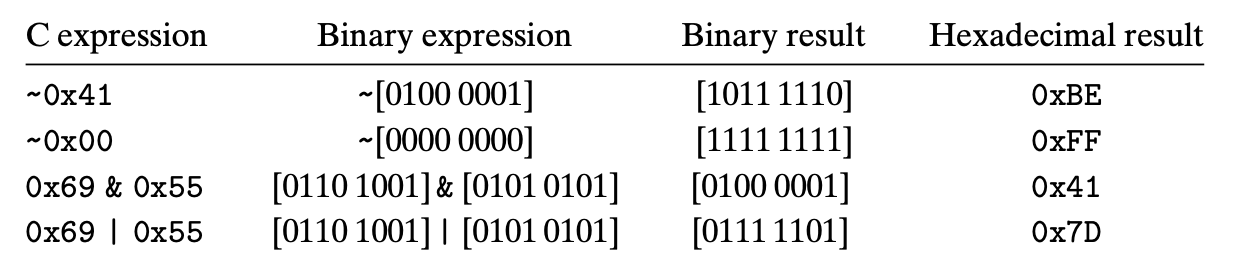

Bit-level Operations in C

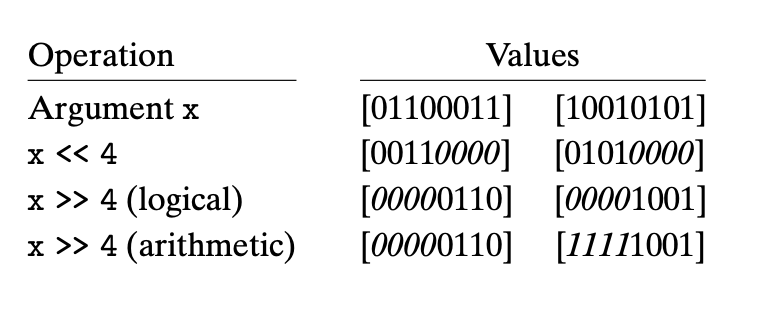

Shift Operation

Integer Representations

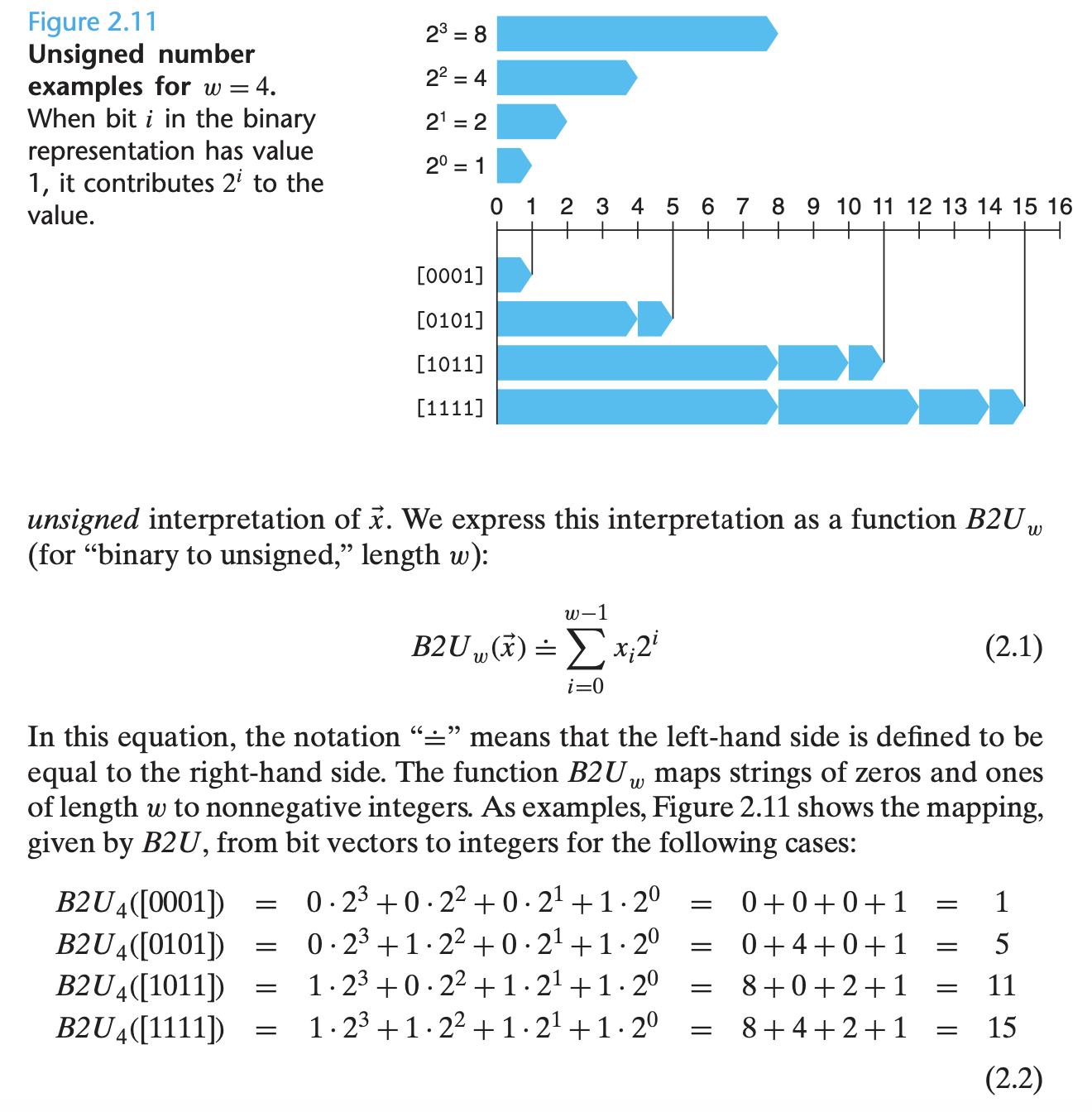

Unsigned Encodings

0 = 0 1 = 1 2 = 10 3 = 11 4 = 100

There are a number of other ways to represent numbers, including floating point and two’s complement.

With numerical operations, it is important to consider the bounds of the binary representations. With addition of large ints, it is easy to overflow.

This chapter runs through addition, subtraction, multiplying by constants, dividing by powers of two, and a number of different operations.

3. Machine-Level Representation of Programs

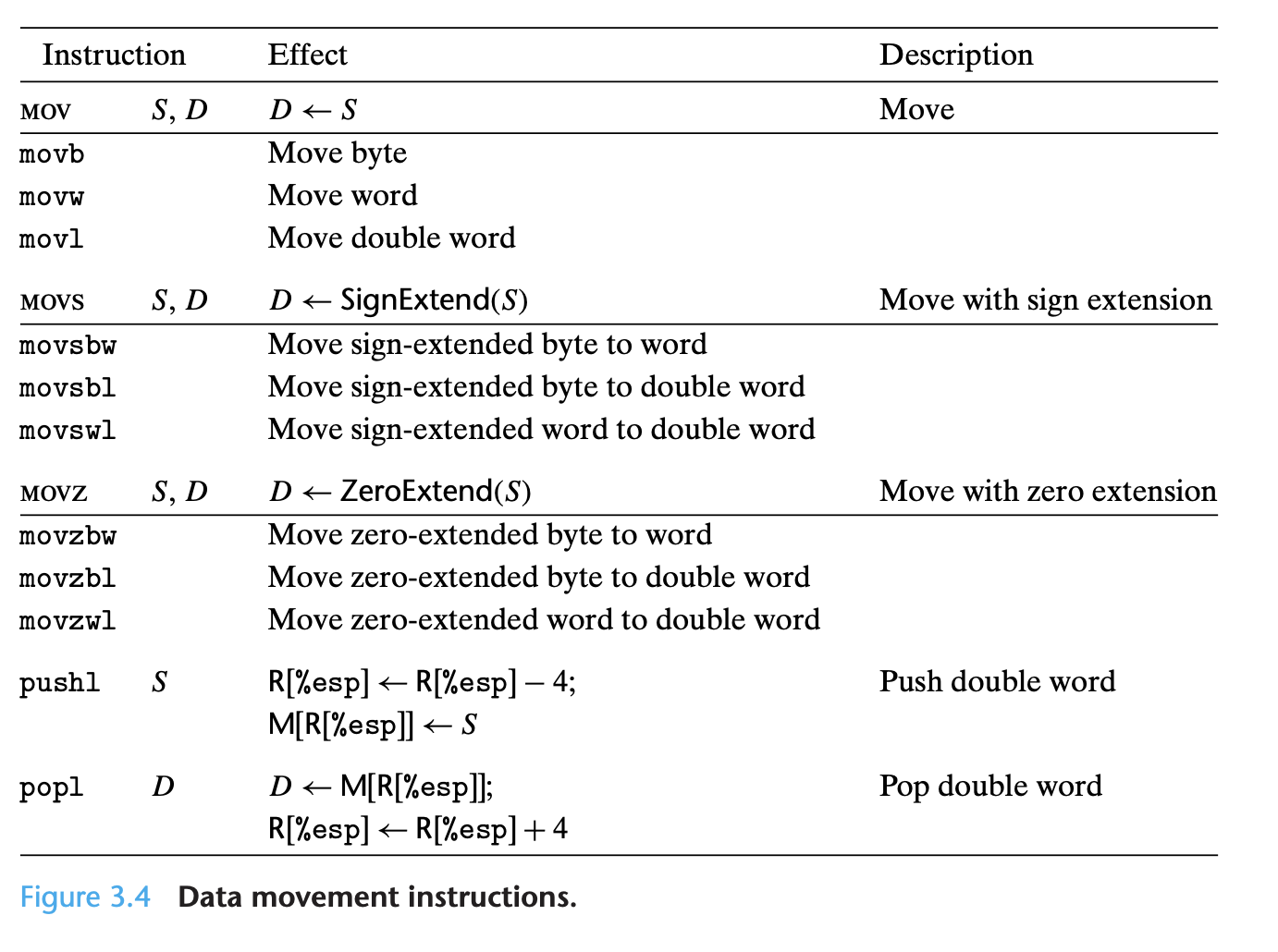

Computers execute machine code, sequences of bytes encoding the low-level op- erations that manipulate data, manage memory, read and write data on storage devices, and communicate over networks. A compiler generates machine code through a series of stages, based on the rules of the programming language, the instruction set of the target machine, and the conventions followed by the operat- ing system. The gcc C compiler generates its output in the form of assembly code, a textual representation of the machine code giving the individual instructions in the program. gcc then invokes both an assembler and a linker to generate the executable machine code from the assembly code. In this chapter, we will take a close look at machine code and its human-readable representation as assembly code.

So why should we spend our time learning machine code? Even though compilers do most of the work in generating assembly code, being able to read and understand it is an important skill for serious programmers. By invoking the com- piler with appropriate command-line parameters, the compiler will generate a file showing its output in assembly-code form. By reading this code, we can under- stand the optimization capabilities of the compiler and analyze the underlying inefficiencies in the code.

Whereas a 32-bit machine can only make use of around 4 gigabytes (232 bytes) of random-access memory, current 64-bit machines can use up to 256 terabytes (248 bytes).

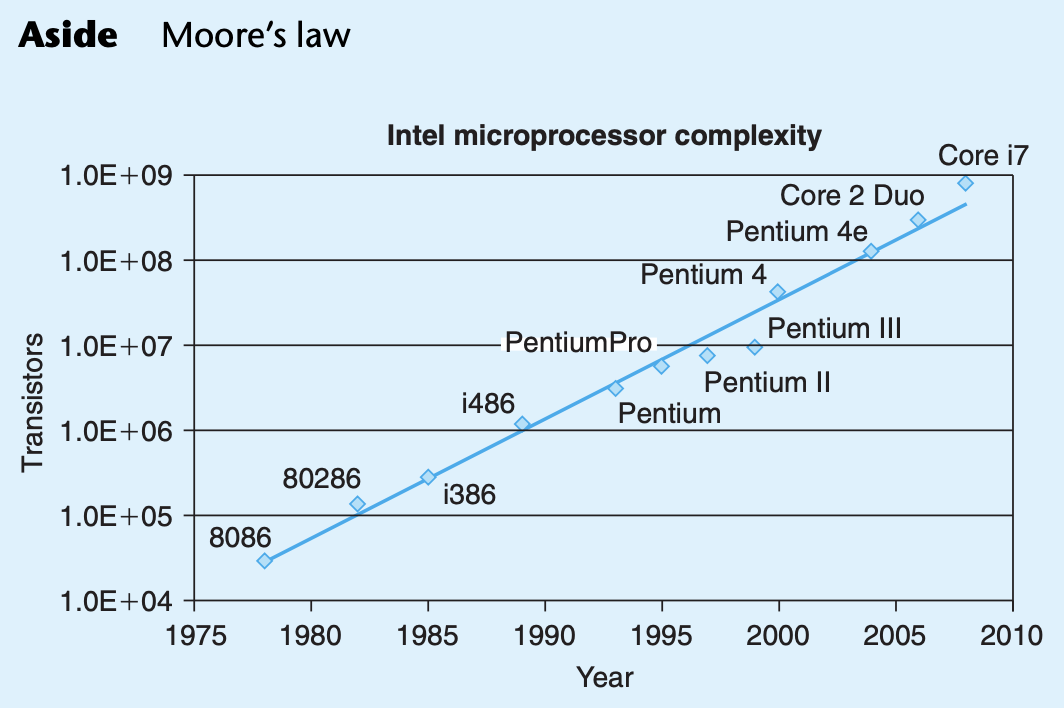

The Intel processor line, colloquially referred to as x86, has followed a long, evolutionary development. It started with one of the first single-chip, 16-bit microprocessors, where many compromises had to be made due to the limited capabilities of integrated circuit technology at the time. Since then, it has grown to take advantage of technology improvements as well as to satisfy the demands for higher performance and for supporting more advanced operating systems.

Intel has had several names for their processor line, including IA32, for “Intel Architecture 32-bit,” and most recently Intel64, the 64-bit extension to IA32, which we will refer to as x86-64.

unix> *gcc -O1 -o p p1.c p2.c*

The gcc command actually invokes a sequence of programs to turn the source code into executable code. First, the C preprocessor expands the source code to include any files specified with #include commands and to expand any macros, specified with #define declarations. Second, the compiler generates assembly- code versions of the two source files having names p1.s and p2.s. Next, the assembler converts the assembly code into binary object-code files p1.o and p2.o. Object code is one form of machine code—it contains binary representations of all of the instructions, but the addresses of global values are not yet filled in. Finally, the linker merges these two object-code files along with code implementing library functions (e.g., printf) and generates the final executable code file p. Executable code is the second form of machine code we will consider—it is the exact form of code that is executed by the processor.

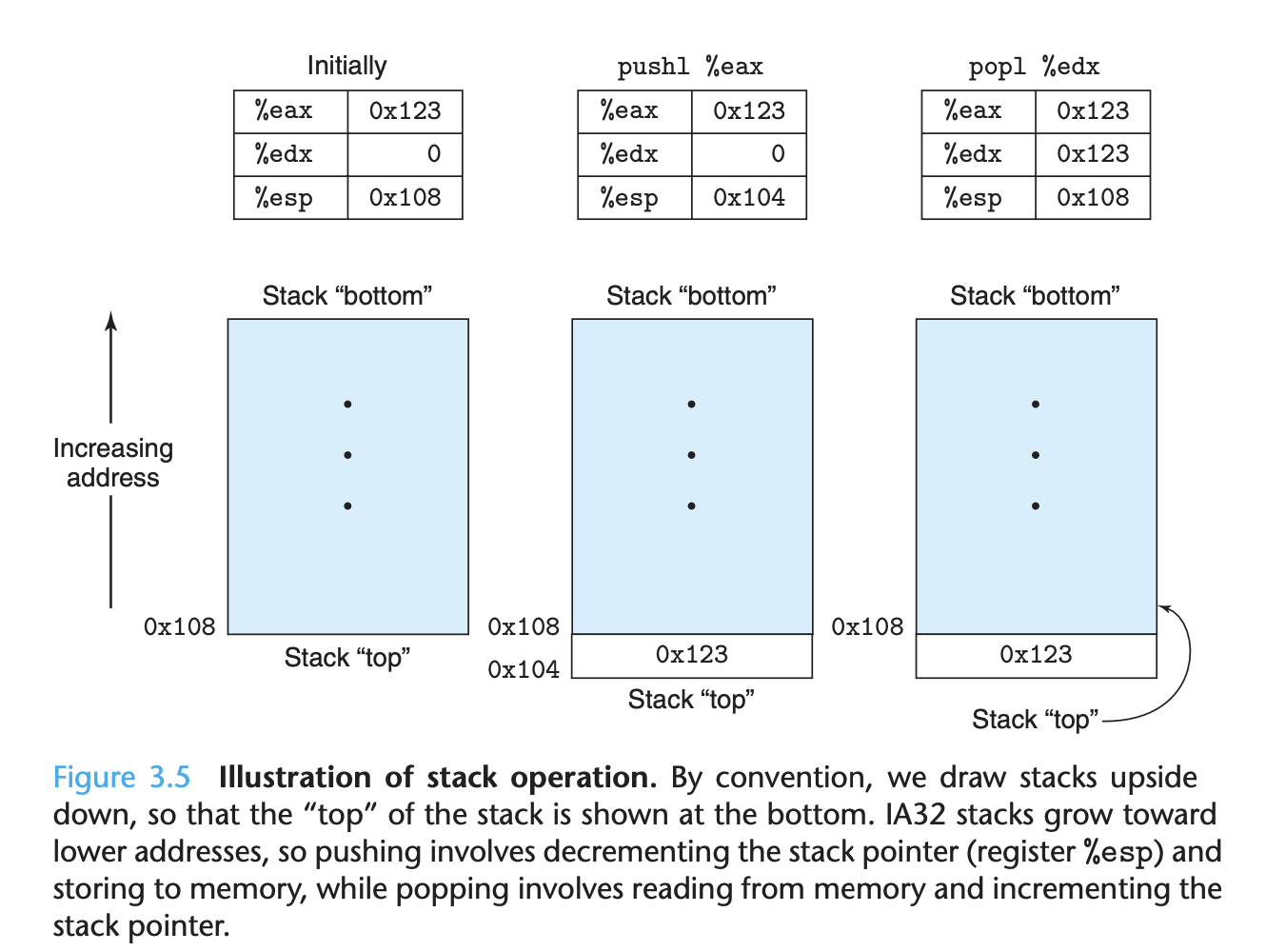

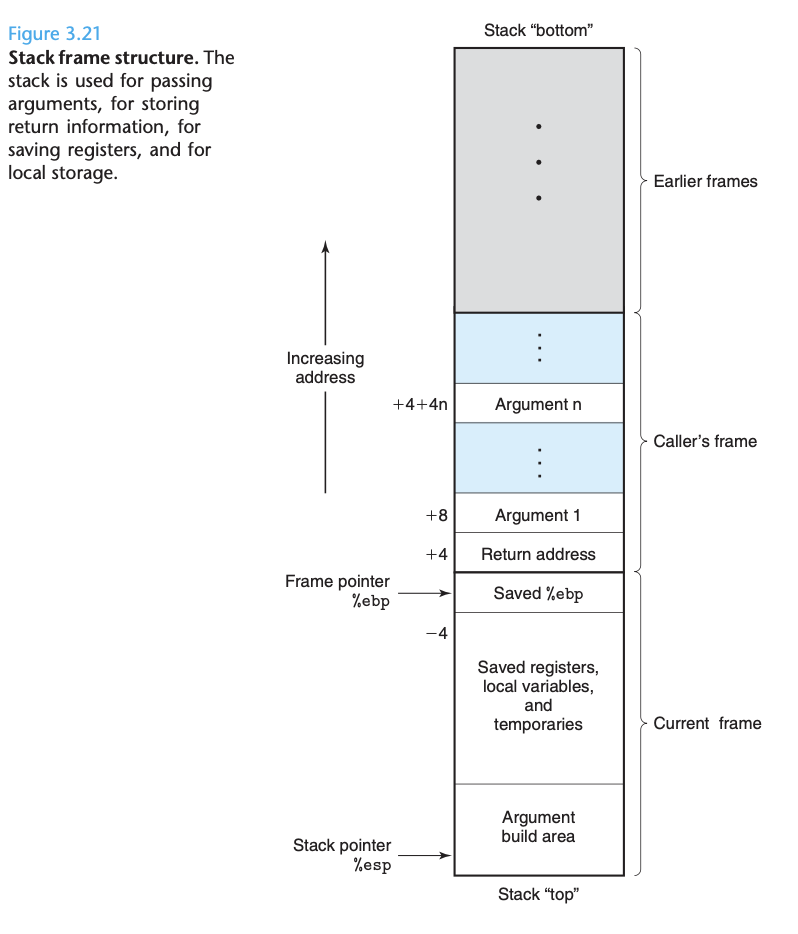

IA32 machine code differs greatly from the original C code. Parts of the processor state are visible that normally are hidden from the C programmer:

- The program counter (commonly referred to as the “PC,” and called %eip in IA32) indicates the address in memory of the next instruction to be executed. - The integer register file contains eight named locations storing 32-bit values. These registers can hold addresses (corresponding to C pointers) or integer data. Some registers are used to keep track of critical parts of the program state, while others are used to hold temporary data, such as the local variables of a procedure, and the value to be returned by a function. - The condition code registers hold status information about the most recently executed arithmetic or logical instruction. These are used to implement con- ditional changes in the control or data flow, such as is required to implement if and while statements. - A set of floating-point registers store floating-point data.

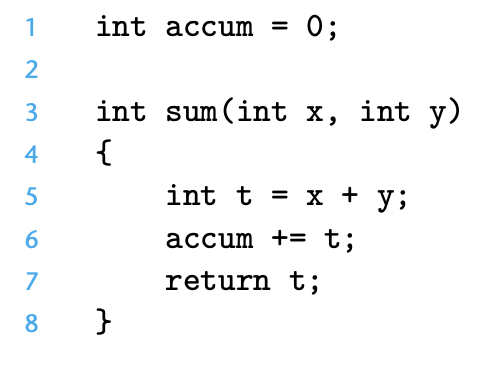

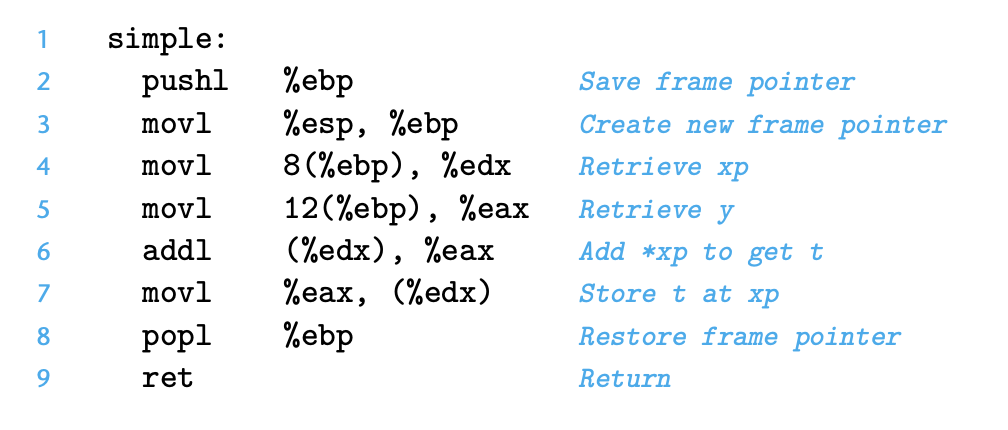

Suppose we write a C code file code.c containing the following procedure definition:

To see the assembly code generated by the C compiler, we can use the “-S” option on the command line:

unix> *gcc -O1 -S code.c*

This will cause gcc to run the compiler, generating an assembly file code.s, and go no further. (Normally it would then invoke the assembler to generate an object- code file.)

The assembly-code file contains various declarations including the set of lines:

sum:

pushl %ebp

movl %esp, %ebp

movl 12(%ebp), %eax

addl 8(%ebp), %eax

addl %eax, accum

popl %ebp

ret

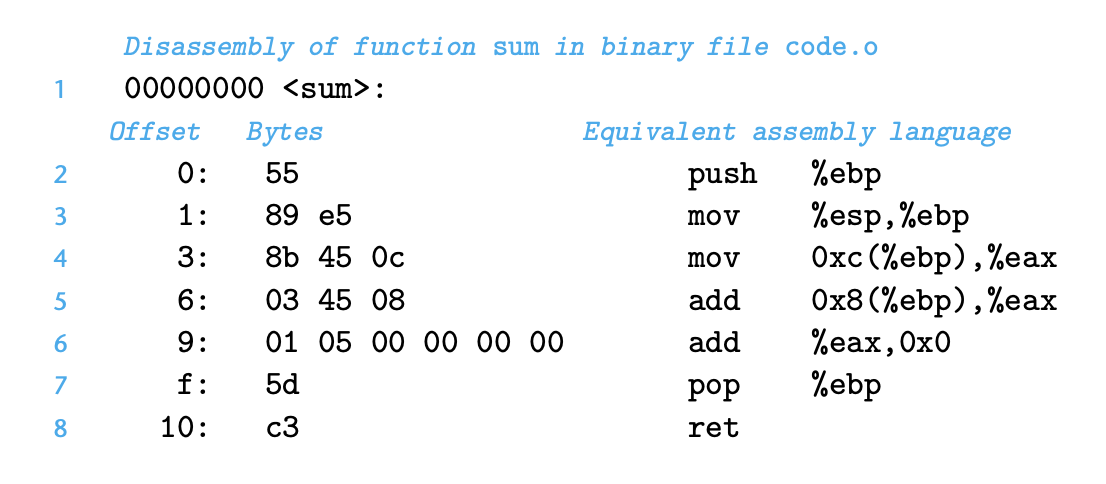

To inspect the contents of machine-code files, a class of programs known as disassemblers can be invaluable. These programs generate a format similar to assembly code from the machine code. With Linux systems, the program objdump (for “object dump”) can serve this role given the ‘-d’ command-line flag:

unix> objdump -d code.o

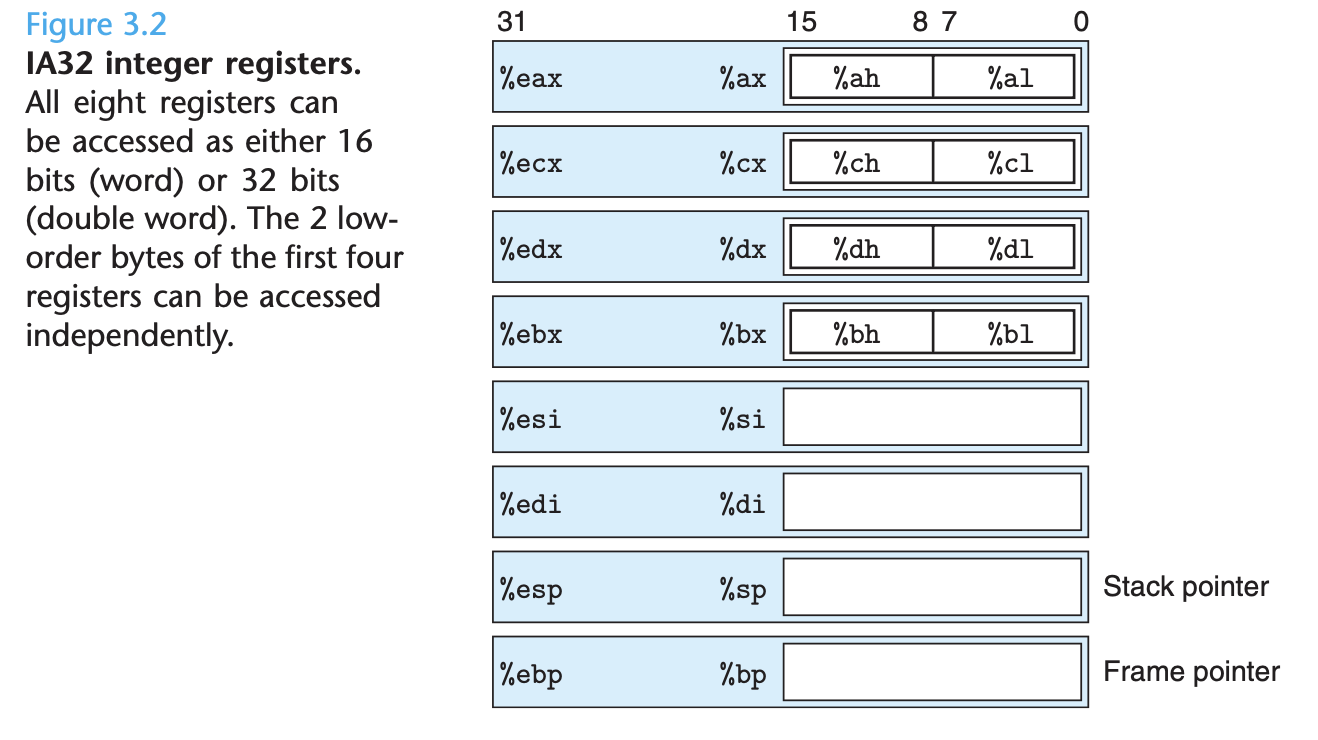

An IA32 central processing unit (CPU) contains a set of eight registers storing 32-bit values. These registers are used to store integer data as well as pointers. Figure 3.2 diagrams the eight registers.

So far, we have only considered the behavior of straight-line code, where instruc- tions follow one another in sequence. Some constructs in C, such as conditionals, loops, and switches, require conditional execution, where the sequence of opera- tions that gets performed depends on the outcomes of tests applied to the data. Machine code provides two basic low-level mechanisms for implementing condi- tional behavior: it tests data values and then either alters the control flow or the data flow based on the result of these tests.

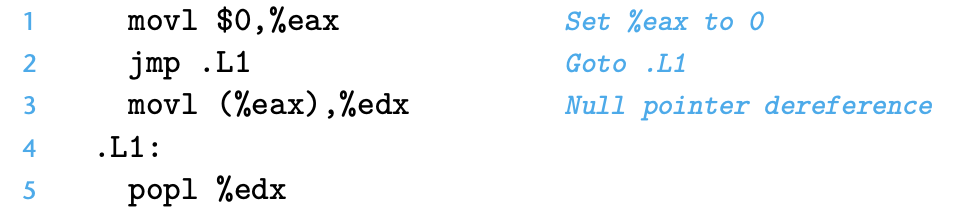

Under normal execution, instructions follow each other in the order they are listed. A jump instruction can cause the execution to switch to a completely new position in the program. These jump destinations are generally indicated in assembly code by a label. Consider the following (very contrived) assembly-code sequence:

The instruction jmp .L1 will cause the program to skip over the movl instruc- tion and instead resume execution with the popl instruction. In generating the object-code file, the assembler determines the addresses of all labeled instruc- tions and encodes the jump targets (the addresses of the destination instructions) as part of the jump instructions.

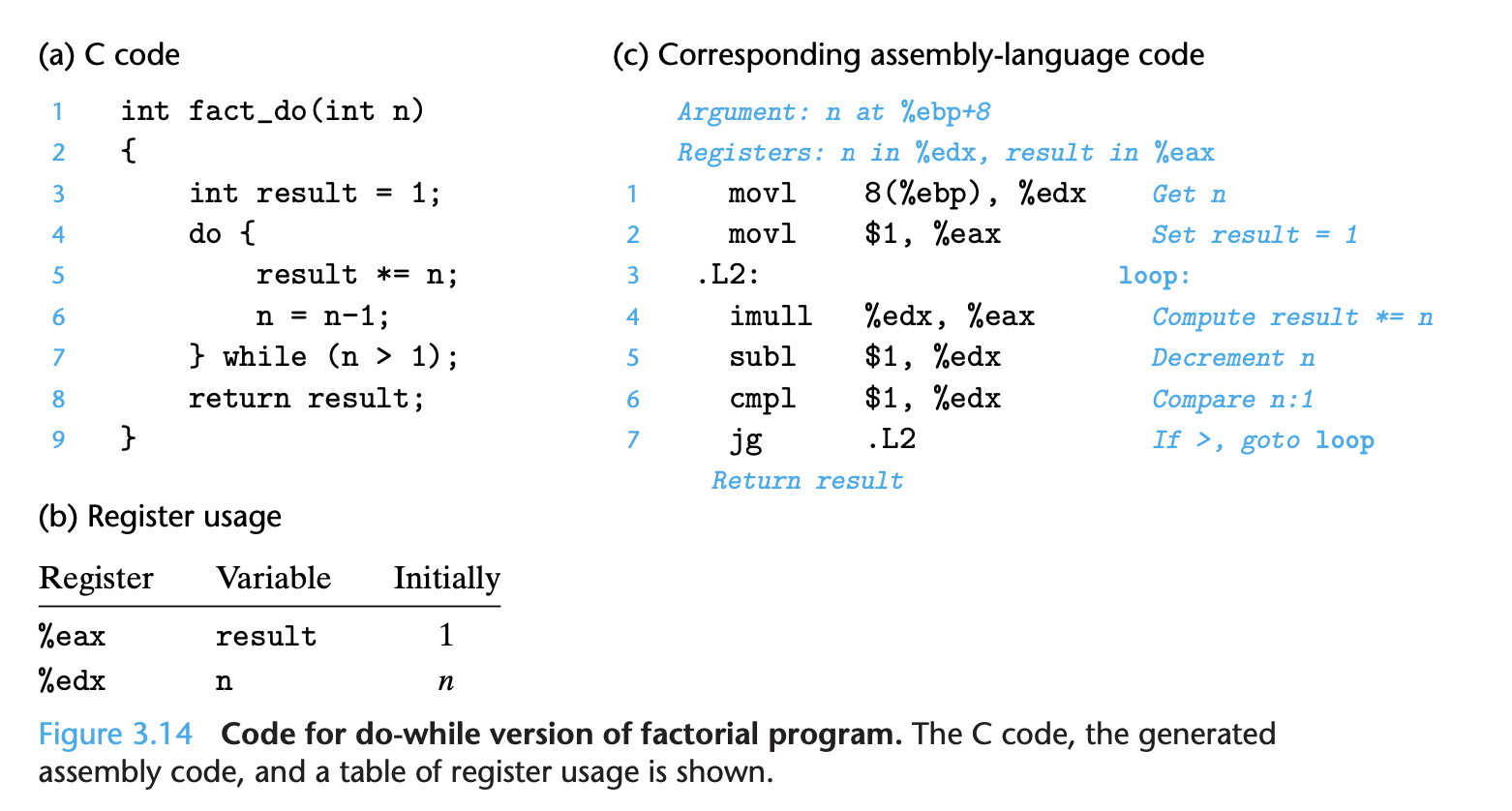

C provides several looping constructs—namely, do-while, while, and for. No corresponding instructions exist in machine code. Instead, combinations of condi- tional tests and jumps are used to implement the effect of loops.

The general form of a do-while statement is as follows: do

body-statement while (test-expr);

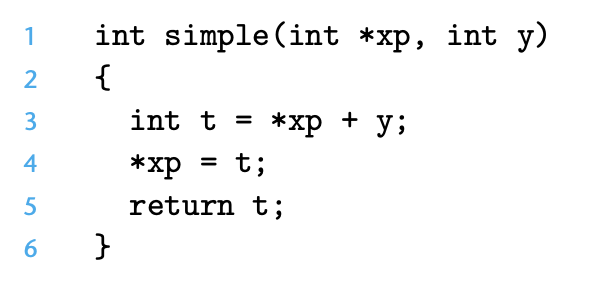

Pointers:

Pointers are a central feature of the C programming language. They serve as a uniform way to generate references to elements within different data structures. Pointers are a source of confusion for novice programmers, but the underlying concepts are fairly simple.

- Every pointer has an associated type

- Every pointer has a value

- Pointers are created with the & operator

- Pointers are dereferenced with the * operator

- Arrays and pointers are closely related

- The name of an array can be referenced (but not updated) as if it were a pointer variable

- Casting from one type of pointer to another changes its type but not its value

- Pointers can also point to functions.

4. Processor Architecture

Modern microprocessors are among the most complex systems ever created by humans. A single silicon chip, roughly the size of a fingernail, can contain a complete high-performance processor, large cache memories, and the logic re- quired to interface it to external devices. In terms of performance, the processors implemented on a single chip today dwarf the room-sized supercomputers that cost over $10 million just 20 years ago. Even the embedded processors found in everyday appliances such as cell phones, personal digital assistants, and handheld game systems are far more powerful than the early developers of computers ever envisioned.

- Understanding how the processor works aids in understanding how the overall computer system works. In Chapter 6, we will look at the memory system and the techniques used to create an image of a very large memory with a very fast access time. Seeing the processor side of the processor-memory interface will make this presentation more complete. - Although few people design processors, many design hardware systems that contain processors. This has become commonplace as processors are embed- ded into real-world systems such as automobiles and appliances. Embedded- system designers must understand how processors work, because these sys- tems are generally designed and programmed at a lower level of abstraction than is the case for desktop systems. - You just might work on a processor design. Although the number of companies producing microprocessors is small, the design teams working on those pro- cessors are already large and growing. There can be over 1000 people involved in the different aspects of a major processor design.

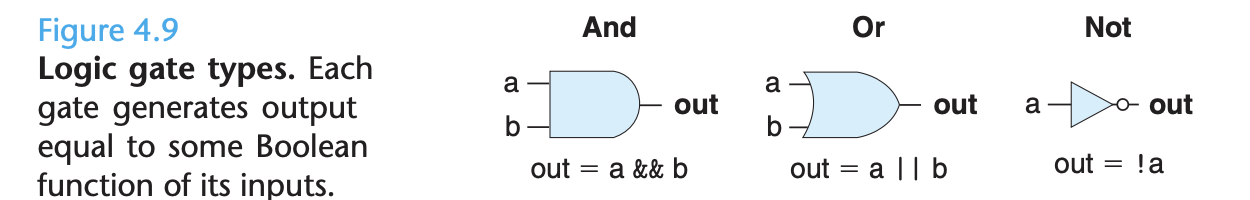

Logic Gates:

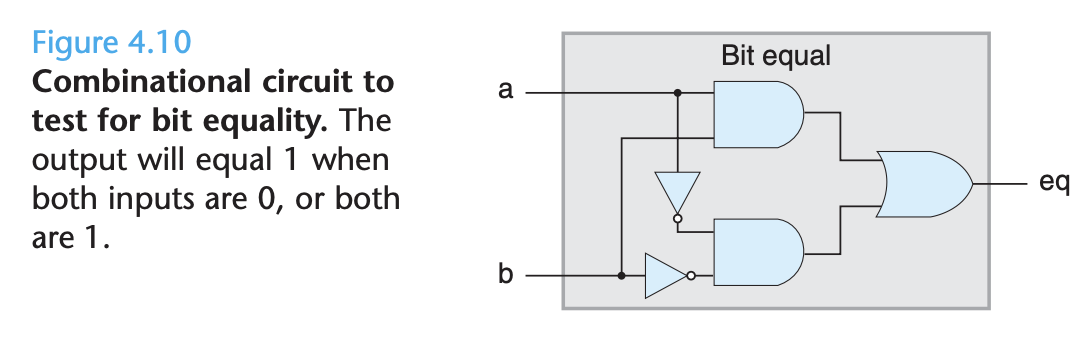

Logic gates are the basic computing elements for digital circuits. They generate an output equal to some Boolean function of the bit values at their inputs.

By assembling a number of logic gates into a network, we can construct compu- tational blocks known as combinational circuits. Two restrictions are placed on how the networks are constructed:

- The outputs of two or more logic gates cannot be connected together. Other- wise, the two could try to drive the wire in opposite directions, possibly causing an invalid voltage or a circuit malfunction. - The network must be acyclic. That is, there cannot be a path through a series of gates that forms a loop in the network. Such loops can cause ambiguity in the function computed by the network.

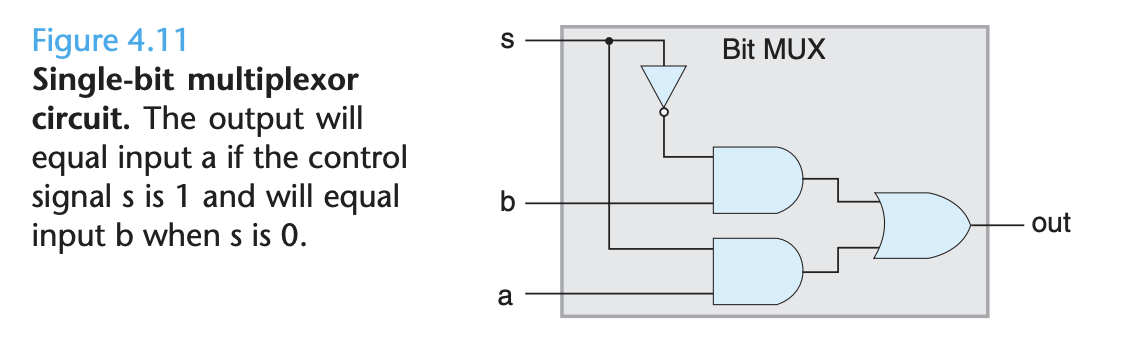

A multiplexor selects a value from among a set of different data signals, depending on the value of a control input signal. In this single-bit multiplexor, the two data signals are the input bits a and b, while the control signal is the input bit s. The output will equal a when s is 1, and it will equal b when s is 0. In this circuit, we can see that the two And gates determine whether to pass their respective data inputs to the Or gate.

Clocked registers (or simply registers) store individual bits or words. The clock signal controls the loading of the register with the value at its input.

Random-access memories (or simply memories) store multiple words, using an address to select which word should be read or written. Examples of random-access memories include (1) the virtual memory system of a processor, where a combination of hardware and operating system software make it appear to a processor that it can access any word within a large address space; and (2) the register file, where register identifiers serve as the addresses. In an IA32 or Y86 processor, the register file holds the eight program registers (%eax, %ecx, etc.)

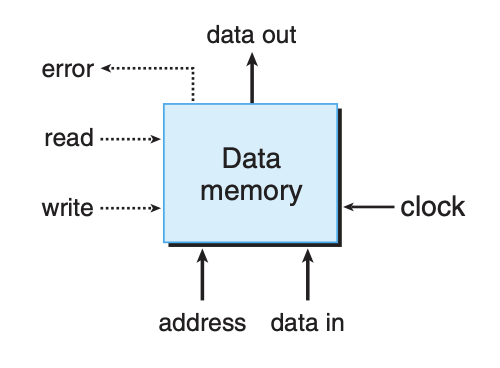

Our processor has a random-access memory for storing program data, as illustrated below:

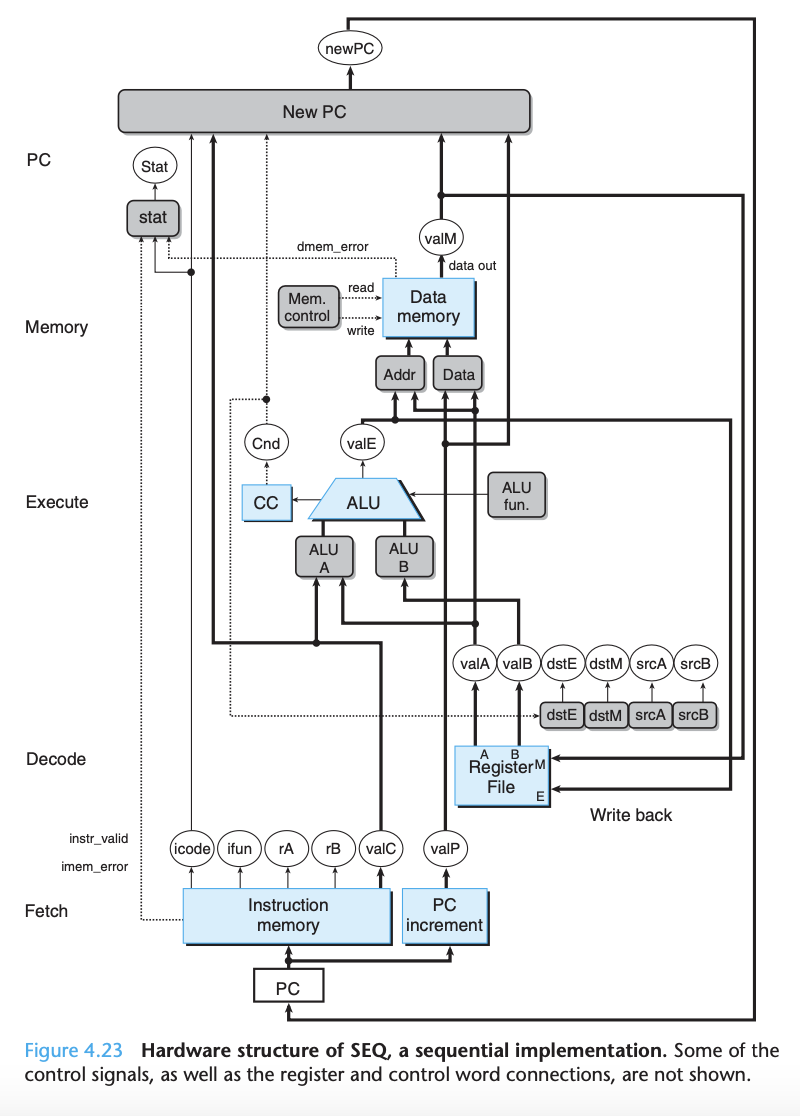

Fetch: The fetch stage reads the bytes of an instruction from memory, using the program counter (PC) as the memory address. From the instruction it extracts the two 4-bit portions of the instruction specifier byte, referred to as icode (the instruction code) and ifun (the instruction function).

Decode: It possibly fetches a register specifier byte, giving one or both of the register operand specifiers rA and rB. It also possibly fetches a 4-byte constant word valC. It computes valP to be the address of the instruction following the current one in sequential order. That is, valP equals the value of the PC plus the length of the fetched instruction.

Execute: The decode stage reads up to two operands from the register file, giving values valA and/or valB. Typically, it reads the registers designated by instruction fields rA and rB, but for some instructions it reads register %esp.

Memory: In the execute stage, the arithmetic/logic unit (ALU) either performs the operation specified by the instruction (according to the value of ifun), computes the effective address of a memory reference, or increments or decrements the stack pointer. We refer to the resulting value as valE. The condition codes are possibly set. For a jump instruction, the stage tests the condition codes and branch condition (given by ifun) to see whether or not the branch should be taken.

Write back: The memory stage may write data to memory, or it may read data from memory. We refer to the value read as valM. PC update: The write-back stage writes up to two results to the register file. The PC is set to the address of the next instruction.

5. Optimizing Program Performance

The primary objective in writing a program must be to make it work correctly under all possible conditions. A program that runs fast but gives incorrect results serves no useful purpose. Programmers must write clear and concise code, not only so that they can make sense of it, but also so that others can read and understand the code during code reviews and when modifications are required later.

On the other hand, there are many occasions when making a program run fast is also an important consideration. If a program must process video frames or network packets in real time, then a slow-running program will not provide the needed functionality. When a computation task is so demanding that it requires days or weeks to execute, then making it run just 20% faster can have significant impact. In this chapter, we will explore how to make programs run faster via several different types of program optimization.

We introduce the metric cycles per element, abbreviated “CPE,” as a way to express program performance in a way that can guide us in improving the code. CPE measurements help us understand the loop performance of an iterative program at a detailed level. It is appropriate for programs that perform a repetitive computation, such as processing the pixels in an image or computing the elements in a matrix product.

The sequencing of activities by a processor is controlled by a clock providing a regular signal of some frequency, usually expressed in gigahertz (GHz), billions of cycles per second. For example, when product literature characterizes a system as a “4 GHz” processor, it means that the processor clock runs at 4.0 × 109 cycles per second. The time required for each clock cycle is given by the reciprocal of the clock frequency. These typically are expressed in nanoseconds (1 nanosecond is 10−9 seconds), or picoseconds (1 picosecond is 10−12 seconds). For example, the period of a 4 GHz clock can be expressed as either 0.25 nanoseconds or 250 picoseconds.

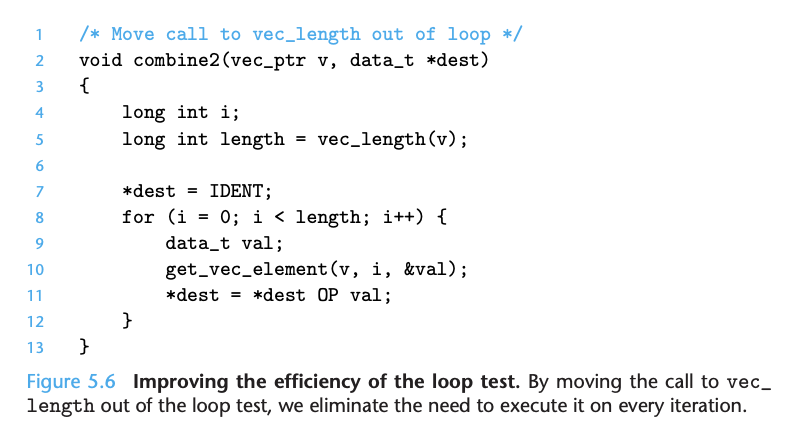

This optimization is an instance of a general class of optimizations known as code motion. They involve identifying a computation that is performed multiple times (e.g., within a loop), but such that the result of the computation will not change. We can therefore move the computation to an earlier section of the code that does not get evaluated as often. In this case, we moved the call to vec_length from within the loop to just before the loop.

Methods for Optimization:

-

Eliminating loop inefficiencies

- Avoid steps that occur in loops that could just occur once, before the loop

-

Reducing procedure calls

- This can enhance performance, especially in performance-critical applications, by decreasing the overhead associated with calling a procedure, which includes the time spent in handling the call stack, passing arguments, and returning values.

-

Eliminating unneeded memory references

- This can improve performance by minimizing the latency and overhead associated with memory access, which can be particularly beneficial in high-performance or real-time applications. Unnecessary memory references can occur due to redundant calculations, excessive variable access, or inefficient data structures.

-

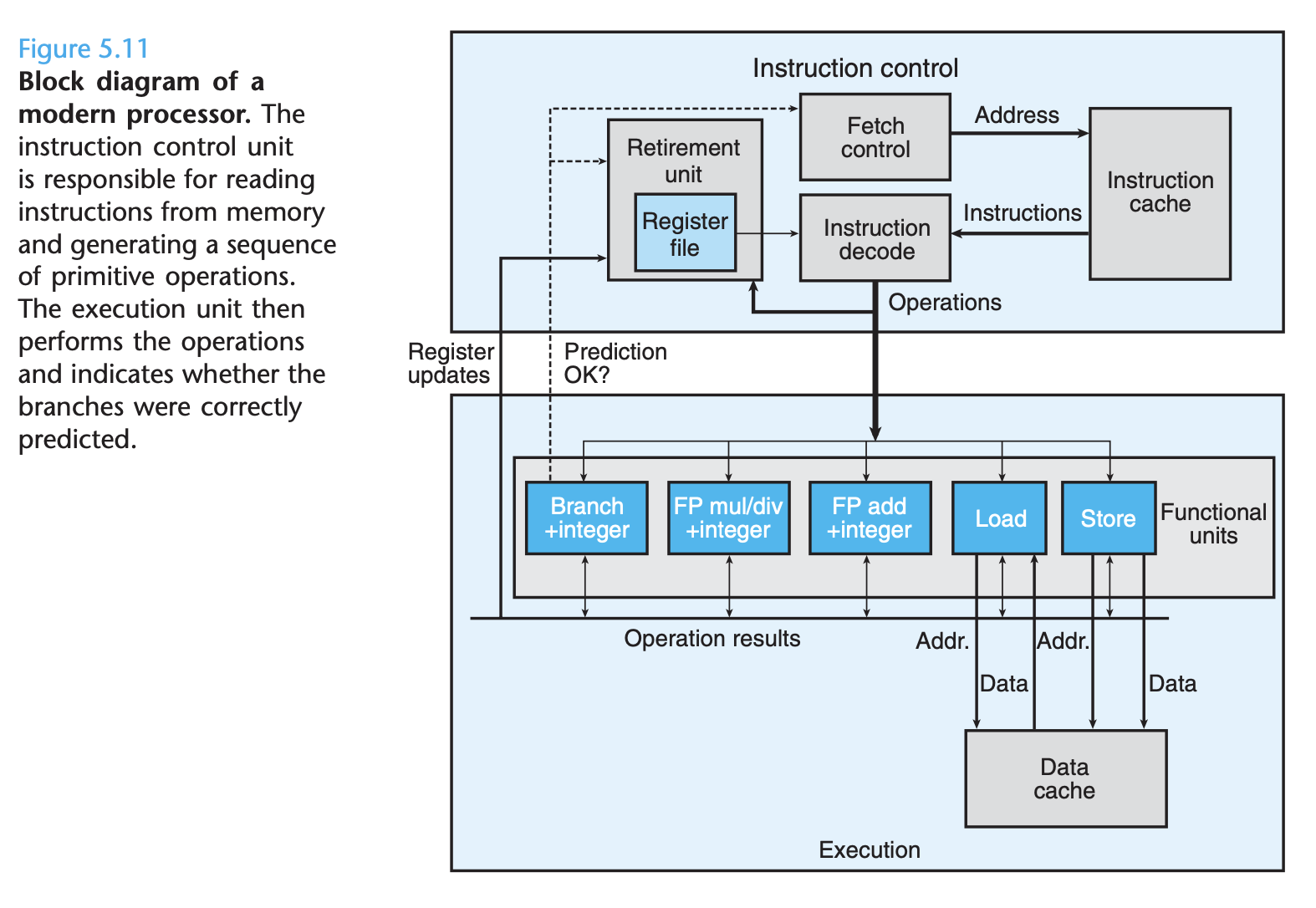

Understanding modern processors

-

Loop unrolling

- Loop unrolling is a program transformation that reduces the number of iterations for a loop by increasing the number of elements computed on each iteration.

-

Enhancing parallelism

- Execute multiple tasks simultaneously rather than sequentially.

6. The Memory Heirarchy

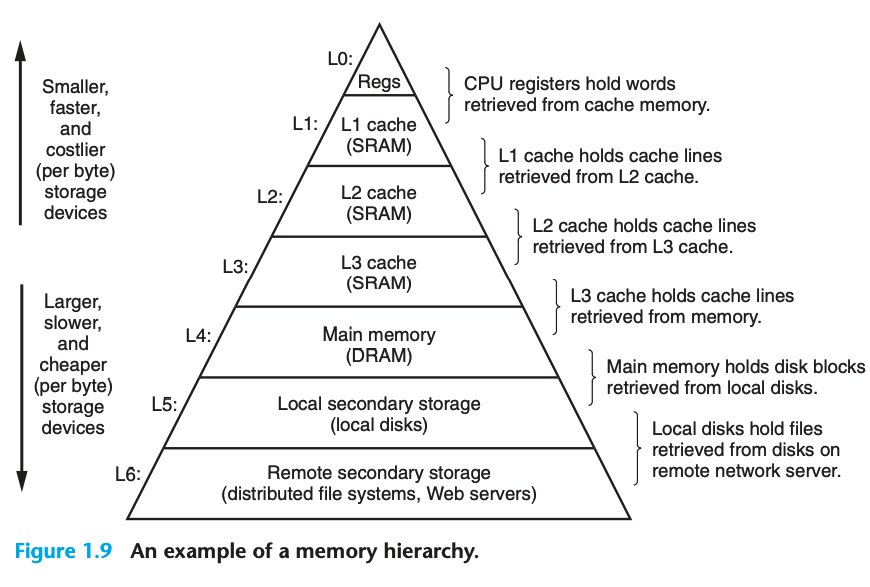

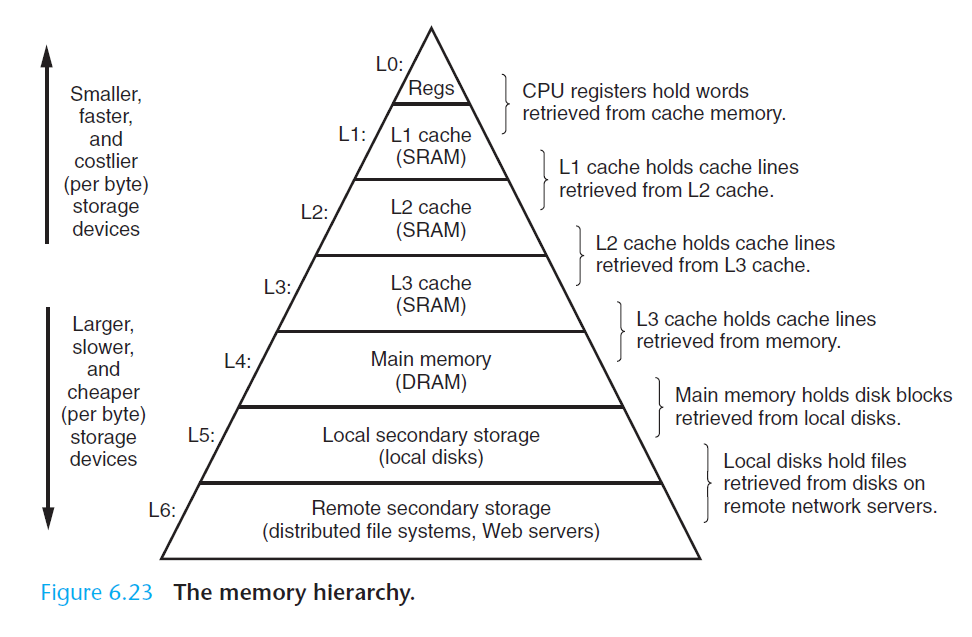

A memory system is a hierarchy of storage devices with different capacities, costs, and access times. Cache memories: small, fast and nearby the CPU act as staging areas for a subset of the data and instructions stored in the relatively slow main memory. If your data is stored on a CPU register, then it can be accessed in zero cycles during the execution of the instruction. If stored in a cache, 1 to 30 cycles. If in main memory, 50 to 200 cycles. If on disk, tens of millions of cycles.

Storage Technologies:

- RAM (random access memory) comes in two varieties: static and dynamic

- Static RAM is faster and significantly more expensive

- Typically, a desktop system will have no more than a few MB of SRAM, but hundreds or thousands of DRAM (note that this book is slightly dated)

- Static RAM stores each bit in a bistable memory cell, where it can be stable to either side, but can also be in an unstable state

- Dynamic RAM stores each bit as a charge on a capacitor. The capacitor is very small. DRAM is very sensitive to any disturbance.

- Conventional DRAMs - the cells or bits are partitioned into d supercells, each consisting of w DRAM cells. A d x w DRAM stores a total of d w bits of information.

- DRAMs and SRAMs are volatile in the sense that they lose their information if the supply voltage is turned off. Nonvolatile memories, on the other hand, retain their information even when they are powered off.

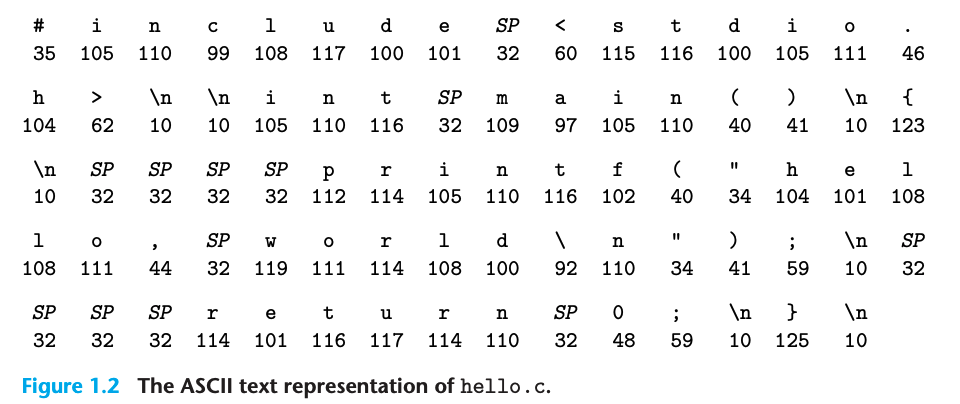

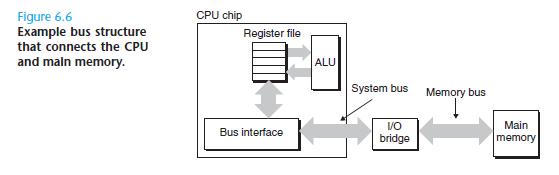

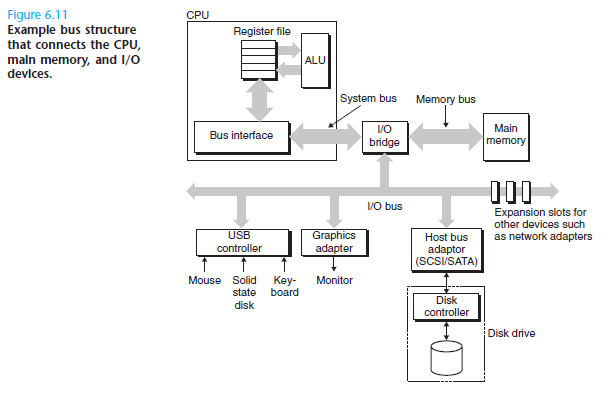

- Buses: data flows back and forth between the processor and the DRAM main memory over shared electrical conduits called buses. Each transfer of data between the CPU and memory is accomplished with a series of steps called a bus transaction.

- A bus is a collection of parallel wires that carry address, data, and control signals.

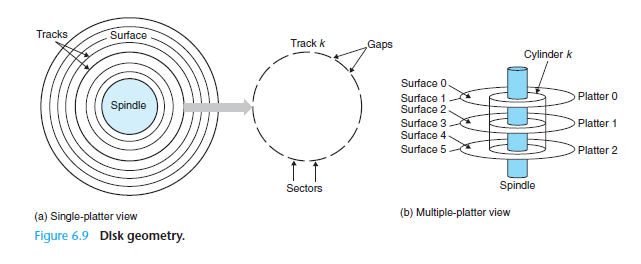

- Disks are storage devices that hold enormous amounts of data, but take much longer to read from.

- I/O devices such as graphics cards, monitors, mice, keyboards, and disks are connected to the CPU and main memory using an I/O bus.

- A solid state disk is a storage technology, based on flash memory.

- Consider the tradeoffs of different storage technologies in terms of price and performance.

- Over time, storage has gotten much less expensive, but not much faster.

Locality

- Locality is referencing data items that are near other recently referenced data items or that were recently referenced themselves.

- Temporal locality: if a memory location is referenced once, it is likely to be referenced again multiple times in the near future.

- Spatial locality: a memory location is referenced once, then the program is likely to reference a nearby memory location in the near future.

- Programs with good locality run faster than programs with poor locality.

- A function such as sumvec that visits each element of a vector sequentially is said to have a stride-1 reference pattern (with respect to the element size). We will sometimes refer to stride-1 reference patterns as sequential reference patterns. Visiting every kth element of a contiguous vector is called a stride-k reference pattern.

- Programs that repeatedly reference the same variables enjoy good temporal locality.For programs with stride-k reference patterns, the smaller the stride the better the spatial locality. Programs with stride-1 reference patterns have good spatial locality. Programs that hop around memory with large strides have poor spatial locality. . Loops have good temporal and spatial locality with respect to instruction fetches. The smaller the loop body and the greater the number of loop iterations, the better the locality.

The Memory Hierarchy

- The central idea of a memory hierarchy is that for each k, the faster and smaller storage device at level k serves as a cache for the larger and slower storage device at level k + 1. In other words, each level in the hierarchy caches data objects from the next lower level. For example, the local disk serves as a cache for files (such as Web pages) retrieved from remote disks over the network, the main memory serves as a cache for data on the local disks, and so on, until we get to the smallest cache of all, the set of CPU registers.

- When a program needs a particular data object d from level k + 1, it first looks for d in one of the blocks currently stored at level k. If d happens to be cached at level k, then we have what is called a cache hit. The program reads d directly from level k, which by the nature of the memory hierarchy is faster than reading d from level k + 1.

- If, on the other hand, the data object d is not cached at level k, then we have what is called a cache miss. When there is a miss, the cache at level k fetches the block containing d from the cache at level k + 1, possibly overwriting an existing block if the level k cache is already full. This process of overwriting an existing block is known as replacing or evicting the block. The block that is evicted is sometimes referred to as a victim block. The decision about which block to replace is governed by the cache’s replacement policy. For example, a cache with a random replacement policy would choose a random victim block. A cache with a least-recently used (LRU) replacement policy would choose the block that was last accessed the furthest in the past.